Scientists have discovered what appear to be six huge galaxies from the early universe. The objects are so huge that they may alter our understanding of how galaxies form.

The findings, published in Nature, make use of data from the James Webb Space Telescope’s infrared-sensing equipment to reconstruct what the cosmos looked like 13.5 billion years ago—when it was only 3% the age it is now. The potential galaxies were somehow as developed as our 13 billion-year-old Milky Way galaxy just 500 to 700 million years after the big bang.

According to the study, the combined mass of the stars inside each of these objects is many billion times greater than the mass of the sun. One of them in particular could have a mass that is up to 100 billion times that of our sun. In contrast, the Milky Way has 60 billion suns’ worth of stars in it.

“You shouldn’t have had time to make things that have as many stars as the Milky Way that fast,” says Erica Nelson, an astrophysicist at the University of Colorado Boulder and a co-author of the study. “It’s just crazy that these things seem to exist.”

Only tiny, young galaxies were anticipated to be discovered at this early stage of the universe’s history. It’s unclear how these “monsters” managed to “fast-track to maturity.”

The majority of cosmological theories state that galaxies originate from tiny clouds of dust and stars that gradually grow in size. According to the belief, matter progressively came together in the early universe. But that doesn’t explain the enormous size of the recently discovered objects.

“The revelation that massive galaxy formation began extremely early in the history of the universe upends what many of us had thought was settled science,” says Joel Leja, an astronomer and astrophysicist at Penn State and a co-author of the study, in a statement. “We’ve been informally calling these objects ‘universe breakers’—and they have been living up to their name so far.”

A shred of doubt

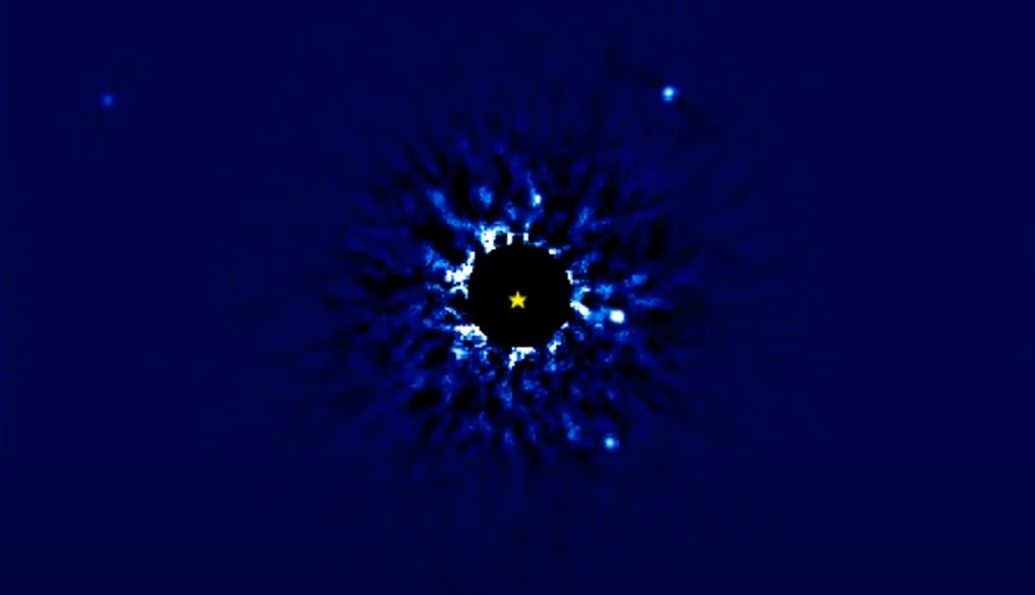

Yet, it may not be necessary to completely revise cosmology just yet: The scientists speculate that some of the objects could be hidden supermassive black holes, and that what the photographs appear to show as brightness may actually be gas and dust being drawn in by their gravity.

The researchers might capture a spectrum image of the objects they’ve identified to confirm their findings. This would make it easier to determine their age. Galaxies from the early cosmos appear “redshifted” to us, implying that the light they emitted was stretched out on its long journey to Earth. The higher the redshift value, the more the light has been stretched and the galaxy is farther away and older. Scientists could use spectroscopy to ascertain whether their prospective galaxies, or “high-redshift candidates,” are as old as they seem to be or if they are mere “intrinsically reddened galaxies” from a more recent period of time.